Post Brexit labour policies threaten UK food security

For such a large company, Kay employs around 3,000 seasonal pickers from Bulgaria, Romania and elsewhere who come here each year to get the harvest in, and without whom the business would simply not exist.

Tesco Direct delivers the workers' groceries; coaches take them out on excursions.“I’m responsible for both a fruit farm and 2,100 beds,” Kay says.

Kay wishes he could reassure his employees in the immediate aftermath of the Brexit vote, but 11 months on their status is no clearer. Indeed, this tidy little village could now stand as a blunt symbol for one of the most serious but little talked about issues arising from the Brexit negotiations: the continued ability of this country to feed itself, if the deal goes wrong.

Opponents of EU membership talked during the referendum campaign about sovereignty and control. They railed against the free movement of labour. What they didn’t mention is the way the British food supply chain has, over the past 30 years, become increasingly reliant on workers from elsewhere, both permanent residents and seasonal labour.

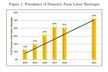

Last month, as parliament wrapped up for the general election, the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Select Committee quietly published a short paper called Feeding the Nation: Labour Constraints. As it reported, around 20% of all employees in British agriculture come from abroad, these days mostly Romania and Bulgaria, while 63% of all staff employed by members of the British Meat Processors Association are not from the UK.

If free movement of labour stops, the British food industry won’t just face difficulties. Some parts could shudder to a halt. Shelves could be emptied. Prices could shoot up. And right now, none of those charged with negotiating Britain’s exit from the EU are making promises that this scenario will be averted.

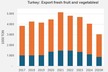

The soft-fruit business of which Hall Hunter is a part is right at the sharp end of that. “From February to November we need 29,000 seasonal workers across the sector,” says Laurence Olins, chair of British Summer Fruits, the crop association for berries, which account for one in every £5 spent on fruit in the UK.

“And 95% of those are non-UK EU citizens.” The industry has tried to get UK nationals to do the work but they’re simply not interested. “Our hope is for some sort of permit scheme,” Olins says. “But if, say, we get only half the permits we need, we will simply have only half the size of the industry.” The 29,000 non-UK workers they have are therefore vital. And, what’s more, the number required is growing.

According to him, what matters is not those living here full-time but the seasonal workforce that comes and goes. Until 2013, there was a seasonal-labour permit scheme which, ironically, was abolished, because the EU free movement system was deemed to be working so well. A replacement would be needed. Pushed for a number of permits required, Wright suggests “around half a million”.

Read more at theguardian.com