The Australian Farm Institute is concerned that the horticulture industry's ability to keep functioning and grow into the future may be influenced by populist movements, rather than science-based evidence.

Speaking at the Protected Cropping Conference, Executive Director Richard Heath has highlighted the growing "Dunning–Kruger effect" trend, which basically means the less a person knows the more they think they know. He explained that it is not a real issue until it is combined with 'democratic society', where the same people are sitting on juries, voting for governments - and the effect is starting to have some perverse and dangerous activities in regulatory decisions.

"So, the true knowledge to be informed in terms of what sensible outcome for policy is that is informed by evidence is difficult," Mr Heath said. "In the horticulture space, we are starting to get into dangerous territory in terms of perverse outcomes that are limiting our ability, not just as a group of agriculture, but as a human race to keep progressing and doing more innovation."

He added that this effect is being used as a 'tactic' in a lot of marketing activities.

"There is a lot of research around this now, because people are trying to understand it because it is particularly relevant to the populist politics around the world at the moment," he said. "Where you are getting very big influential people in positions of power that obvious lack of understanding about what they are talking about - but do it with such confidence and bring people along with them. Today, you are getting GMO free water and salt marketed, because it is targeting that assumed knowledge, by the people who think they know everything about a complex issue, are easy targets for misleading messaging. It's frustrating for people who want to deal with science."

AFI is small independent agriculture policy research organisation, and its mission is finding any evidence base. Mr Heath says he has been asked to talk about community trust than any other topic this year.

"Everyone is seeking to understand what community trust is, how to manage it, and how to participate in this environment" he said. "I'm going to quote Deanna Lush from AgCommunicators said about community trust: 'social licence, right to farm, freedom to operate, trust in agriculture goes by many names, but at its centre is a group of people who are uncertain whether they can trust farmers to produce food in a way that is in the best interest of people, animals and the planet'. What that leads to is this change to freedom to operate, where this disruptive element of community's trust starts to come into play."

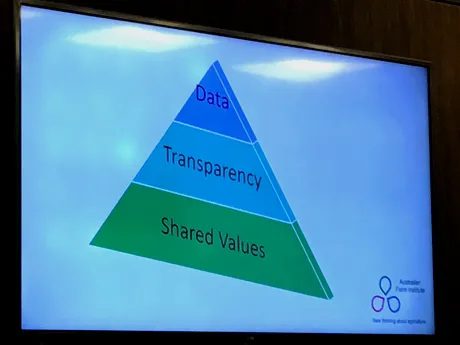

Referring to a diagram from the Centre of Food Integrity in the United States, Mr Heath says social licence, freedom to operate and trust are different.

"For me, trust is the most important thing as an industry, that we need to start with and to concentrate on," he said. "Trust is derived by three main things; someone gives you trust if they have confidence that you share their values. If someone shares values with you, then you are on the front foot. You also need confidence, which is the science and technical capacity - or the facts and evidence of what you are doing. There is also influential others, which is how other people that you trust feel about the issue. They all feed into trust and if you can't maintain that trust or lose that trust, then your social licence becomes threatened and that impacts on your freedom to operate. So, it all begins with trust."

To further illustrate his point, went onto explain the finding from the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) that Glyphosate was a carcinogen.

"The IARC has only ever found that one substance in the thousands that they have looked at, that is not carcinogenic," Mr Heath said. "That got a lot of publicity, as you can imagine, that Glyphosate is something to be concerned about. Now the IARC process that they use is a hazard-based approach, they are looking at whether something is a potential hazard. That is a potential hazard. A hammer is a potential hazard. But is it a risk? It is only a risk if not used appropriately. A hammer is a risk because you could hit things with it. So, the IARC is going to only find one substance out of the thousands that they look at that is not carcinogenic - because anything is carcinogenic at the right level. The dose makes the poison."

He went onto say all of the other international studies that have been conducted into the substance, found that there was no risk if used appropriately.

"But that doesn't matter, because what gets communicated out of that," he said. "A study on French newspapers, where this was a massive issue, which quantified what was talked about in the newspapers and 73 per cent of the time the IARC report was quoted. Why is this the case? The shared values (the community has) in this is about the fear of cancer and big organisation. So those things are much easier to communicate at the shared values and influential others level."

What that leads to, according to Mr Heath, is the court cases like the ones brought against Monsanto, in the United States involving that Glyphosate causing cancer. But the problem he raises, is that juries don't deal with science, and there is nothing in the findings that have reset the science, or that have delivered new science.

"Juries interpret what they see and make a finding on that," he said. "So, it is a representation of our community expectations and understandings, as it should be, on the information that is put to them. So, trust is difficult in the current environment because the competence circle (science and facts), is small, and the confidence and influential others are big and getting increasingly important. It can lead to really perverse, illogical, weird, nonsensical arguments. There is a campaign from an activist organisation against GMOs, that are trying to scare people about Roundup in whisky. Now, we know alcohol is a carcinogenic, it's right at the top - and alcohol can kill you. But (according to them) that’s not what we should be concerned about, instead it's the Roundup. But this is completely understandable; we have shared values about drinking alcohol, but we don't have shared values around Roundup."

He concluded by saying the industry needs to think more about the way in which they are communicating messages with people outside the industry.

"As agriculturists, as scientists, we tend to rely on the data first and tend to respond to issues with evidence, and overwhelm people with evidence," Mr Heath said. "That should be the top of a pyramid. First, we need to start with shared values and we need to start by understanding that if we connect with the community on values that we all understand such as sustainability, environment and shared labour. Basically, the one's that need no technical understanding that connect with core belief systems and become a trusted partner on those values. On the next level up we need to be transparent in our industry on how we demonstrate those shared values. We can then feed the evidence onto that."