Over the past five years, the Greek economy has been experiencing another revitalization. After the deep 2008–2012 crisis, which ended a long growth period and caused a GDP collapse, and a stagnation period until 2017, the 2020–2021 pandemic-related crisis was quickly overcome. Yet, according to the Hellenic Statistical Authority, the country's GDP remains far below 2008 levels. What, though, has been happening in Greek agriculture during these years, and how has the fresh produce been affected? To begin with, the cultivated farmland decreased by 22,1% (2.888.000 hectares in 2023).

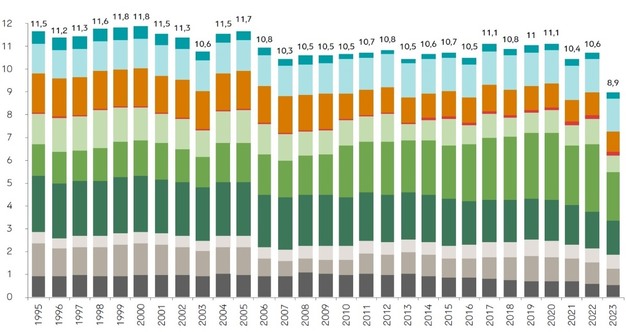

More importantly, however, according to Eurostat data processed by diaNEOsis in its 2024 study, The Agricultural Sector in Greece, the agricultural production value has also not reached pre-2008 levels. Despite the positive trend during 2010–2020, Greek agricultural production has persistently been unable to truly expand. On the contrary, total agricultural output has shown a negative trend over the past 30 years, with an average annual decline of around 0,3%. The year 2023 is excluded from the calculation due to the dramatic impact of Storm Daniel on Greek agriculture; otherwise, the average annual decrease exceeds 0,9%.

© diaNEOsisGraph by diaNEOsis. Value of agricultural production (billion € at constant 2015 prices, base year)

© diaNEOsisGraph by diaNEOsis. Value of agricultural production (billion € at constant 2015 prices, base year)

Light green: Fruit

Dark green: Vegetables

In contrast to overall agricultural production, the specific category of fresh fruit has shown significant growth in production value since 2010, reaching €3,615 billion in 2022 (27,9% of total agricultural production value). During the same period, the production value of vegetables showed a noticeable decline, settling at €1,837 billion (14,2%). At the same time, the value of Greek fruit and vegetable exports has been steadily increasing (driven by fruits), representing 36,5% of the total, also steadily rising, value of Greek agricultural exports in 2023.

Despite the positive exceptions, the overall downward trend in the production value of the Greek agricultural sector raises concern about the future of all its branches. The causes of this negative trend lie both in the structural characteristics of the sector itself and in the broader features of the Greek economy in recent years.

Declining labor productivity

A major cause for concern regarding the prospects of Greek agriculture, reflecting the impact of all the aforementioned factors, is the weakening of its labor productivity. According to diaNEOsis, the gross value added per person employed has fallen sharply since 2020, reversing the slow gains since 2008 and reaching a fifteen-year low of €13,465 in 2023. This corresponds to an average annual decline rate of 0,42%. In the meantime, agricultural employment and its share of total employment have risen since 2020—though still well below 2008–2010 levels—reaching 461,400 people (11%) in 2023. Thus, more people, but lower productivity.

Insufficient investment in capital and new technology

Examining the specific factors that weaken labor productivity in Greek agriculture reveals a wide range of problems and weaknesses, some of which have to do, as we said, with the entire Greek economy. These include limited investment resources, lagging investment in modern technologies, and low levels of R&D activity.

The severe crisis that began in 2008 triggered a pronounced contraction in investment expenditure. According to diaNEOsis, the decline in gross fixed capital formation below the level of capital depreciation during 2010–2021 implied a twelve-year process of capital stock depletion in the Greek economy, resulting in cumulative losses exceeding €94 billion. Furthermore, the coincidence of Greece's prolonged period of underinvestment with an era of rapid technological advances and their widespread integration into production, collectively recognized as the Fourth Industrial Revolution, resulted in a significant lag in the adoption of these technologies by the domestic productive sector.

In this context, it was inevitable that investment spending in Greek agriculture would also be affected. After the historic peak of 2008, investments dropped sharply, even reaching negative formation levels in 2011-2012 and 2014-2015. Since then, a slow recovery toward 2008 levels has been observed, nearly achieved by 2022.

Small and fragmented land holdings eat away at investments

However, this recovery loses its impact on productivity growth when it encounters a key characteristic of Greek agriculture: the very small and fragmented land holdings. According to the latest available data from the Structure of Agricultural Holdings Survey by the Hellenic Statistical Authority, in 2020 the average utilized area of Greek farms barely exceeded 5,3 hectares, showing a downward trend (-2,9% over a decade).

This reality prevents the creation of economies of scale. The high fragmentation into small farms creates an artificially increased need for larger quantities of basic capital equipment. While this may slightly raise total investment spending, the allocation is not efficient—diaNEOsis notes overinvestment in cheap, sometimes second-hand, basic equipment, and underinvestment in more expensive, modern, basic equipment, as well as in supplementary equipment—and the average utilization of the newly acquired gross fixed capital is far below its potential, since it corresponds to a smaller area.

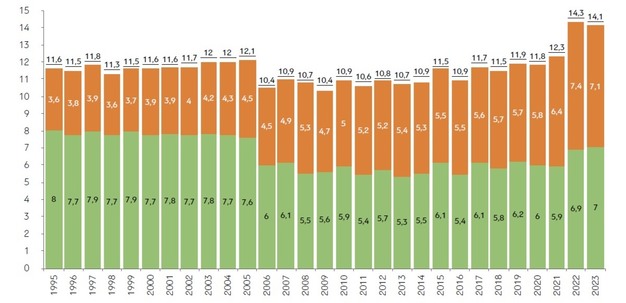

Greece's disadvantage in the international energy market

While both production value and labor productivity in Greek agriculture are declining, the share of intermediate consumption—i.e., the transfer of input cost to the total value of agricultural output—is increasing, also driven by the rising agricultural inputs. According to diaNEOsis, while in 2003 intermediate consumption represented about one-third of agricultural production value, by 2022 it accounted for more than half. While the rise in (largely imported) fertilizer and pesticide costs needs no further analysis as a global trend, energy prices in Greece are a story of their own.

In 2020, Greece completed an EU-driven energy transition, with domestically sourced, cheap lignite, once the dominant energy source, reduced to just 10% of total energy generation. Most power now comes from renewables and imported natural gas, both more expensive than lignite. Moreover, gas prices have also risen sharply since the Russia–Ukraine war began, due to both higher Russian gas prices and the shift from cheaper Russian to more expensive U.S. imports. These factors explain the dramatic rise in the share of intermediate consumption in 2022, a trend unlikely to reverse soon based on current energy market projections.

© diaNEOsisGraph2 by diaNEOsis. Production value, intermediate consumption & GVA of agriculture (billion €, 2024 prices)

© diaNEOsisGraph2 by diaNEOsis. Production value, intermediate consumption & GVA of agriculture (billion €, 2024 prices)

Orange: Ιntermediate consumption

Green: Gross value added

Social and other causes of agricultural abandonment

Other developments linked to the country's recent economic challenges have also been undermining Greek agriculture, though indirectly. Continuous cuts in social policy spending and the reduction of public sector wages have led to understaffing or closure of critical public facilities in rural areas (health units, schools, public administration offices). Natural disaster prevention and agricultural infrastructure (irrigation facilities, rural roads) also remain underfunded. Combined with high unemployment and the harsh yet poorly compensated nature of farm work, these factors contribute to rural depopulation, severe aging of farmers, and a labor shortage—despite a recent increase due to migrants from Asia.

Ιn this context, Greek farmers' income is heavily dependent on EU subsidies. The €1,1 billion in accumulated payments owed by the Greek state to farmers as of 2024 is further constraining the actual economic activity of tens of thousands of small producers. Any reduction in CAP support would add new pressure. Greek farmer organizations have long argued that the CAP's distribution model, allocating funds based on land ownership rather than production, favors large landowners, even for idle land, pushing small farmers toward financial exhaustion and withdrawal.

Ultimately, it appears that the Greek economy, and the country's economic and agricultural policy within the CAP framework, remains intertwined with this negative trajectory. Without measures to improve agricultural productivity and revitalize rural areas, the positive results seen in specific branches, such as fruit production, not only have limited growth potential but are, in fact, built on rather fragile foundations.