When I first came to Suriname, I wanted to make a cold dish. However, I couldn't find a single good tomato. Somewhere, I found a wilted piece of lettuce, which was all that was left. Then it is the chicken-and-egg question: Is it not grown because people don't eat it, or do people not eat it because it is not available? Marnix Maenhoudt proved it was the latter: he now sells 4,000 heads of lettuce a week in Suriname and still comes up short. "You don't always have to wait for them to come and ask for it, because if it's not there, nobody does," he says.

© Pieter Boekhout | FreshPlaza.comAn acre of greenhouse. Plastic with shade cloth underneath

© Pieter Boekhout | FreshPlaza.comAn acre of greenhouse. Plastic with shade cloth underneath

Formerly living in West Flanders, Belgium, and working in automation, Marnix now walks daily among the plants in the foil greenhouses of the Surinamese nursery Intergreens. There, lettuce grows on pyramid-shaped structures, and tomatoes grow in pots. Every day is about production, biological control, buyers, climate, and hydroponics.

© Pieter Boekhout | FreshPlaza.comGrowing tomatoes in pots

© Pieter Boekhout | FreshPlaza.comGrowing tomatoes in pots

"If you bet on one horse, you must be very good," he says when asked why he combines lettuce with tomatoes. "And you never know here: if a disease comes in, you have nothing." He was told he would not be able to grow tomatoes in Suriname. "For me, that's the best motivation there is. I said I could do it. And then I would rather drop dead than be proven wrong." Reflecting, he continues. "After two months, all the plants were dead. But now we are three years on, and I can do it." He managed the same with sweet peppers, trials of which have also been successful, and large-scale cultivation is now on the table.

© Pieter Boekhout | FreshPlaza.comMarnix among the curly lettuce

© Pieter Boekhout | FreshPlaza.comMarnix among the curly lettuce

Bas Slagter, a cultivation consultant closely involved in the project, laughs. Originally from North Holland, he usually works with cauliflowers. For that, too, both men see potential for open-field production. "It's worth its weight in gold. And broccoli, because they love broccoli here. And that is expensive. It comes frozen, or from the better shops. But if you can lower the price a bit, you can sell a lot here, because it's all imported."

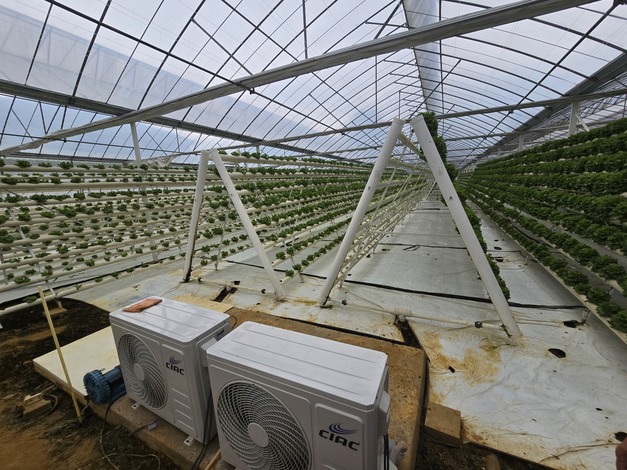

© Pieter Boekhout | FreshPlaza.comIn the new greenhouse, the pyramid system is replaced by cultivation gutters; in the foreground, the water coolers

© Pieter Boekhout | FreshPlaza.comIn the new greenhouse, the pyramid system is replaced by cultivation gutters; in the foreground, the water coolers

And that import is a thorn in their side. "That makes no sense at all," Bas says, and Marnix adds, "That's also the question I always get when I show a beautiful tomato. Is it for export? That mindset is ingrained here. The best produce goes abroad, and here we eat what's left." At Intergreens, it's different. The best tomatoes stay in Suriname. The same goes for the lettuce, now sold in many local shops. "If it's everywhere, and then I still have surplus, I'll think about it," he says.

© Pieter Boekhout | FreshPlaza.comOld tomato plants have just been cleared out

© Pieter Boekhout | FreshPlaza.comOld tomato plants have just been cleared out

Automation

Although Marnix left the automation sector, it still plays an important role in his daily operations. A core element of Intergreens is its data-driven approach. "I have some green fingers, but mostly I can design, program, and optimize systems," he says.

All cultivation data is recorded in detail: treatments, harvests per row, nutrition changes, and planting dates. Harvesting staff note everything down on paper, after which a trusted employee enters the data into the digital system. "Everything down to the comma. So we can see exactly what works and what doesn't."

© Pieter Boekhout | FreshPlaza.comOwn propagation

© Pieter Boekhout | FreshPlaza.comOwn propagation

At first, Marnix thought this would save labor costs, but after a few years in Suriname, he realized it was more important to use technology to ensure crop work was done properly. Staff are difficult to find, and turnover is high, so loyal employees are well rewarded. New employees start at a salary of around USD 300 per month, while experienced staff who prove themselves can earn USD 400 or more. Marnix explains that motivation and commitment matter more than training: "Someone who shows initiative and provides solutions is worth their weight in gold."

Employees involved in maintenance, harvesting, or other critical tasks receive extra rewards. Still, finding the right people is difficult. He gives manual pollination with blowers as an example. "That goes well on day one. And the second day. But after a while, you see that some people position the plants well in the wind and others don't. Then pollination fails anyway."

© Pieter Boekhout | FreshPlaza.comFrom left to right: Bas Slagter, retired Dutch cauliflower grower, but nowadays regularly in Suriname through the PUM foundation for support and advice in the agricultural sector; Marnix Maenhoudt, founder and owner of Intergreens NV; Kenny van Dijk, a Surinamese entrepreneur in agriculture and agricultural machinery, with in the background the refrigerated truck used to deliver everything

© Pieter Boekhout | FreshPlaza.comFrom left to right: Bas Slagter, retired Dutch cauliflower grower, but nowadays regularly in Suriname through the PUM foundation for support and advice in the agricultural sector; Marnix Maenhoudt, founder and owner of Intergreens NV; Kenny van Dijk, a Surinamese entrepreneur in agriculture and agricultural machinery, with in the background the refrigerated truck used to deliver everything

He sighs. "I have no frustrations, that's a dirty word. But when we scale up, we will automate even more. Then one of those trolleys will run, with blower fans." Marnix has big plans for the future. Intergreens' current nursery is considered more of a test site. On an 8-hectare plot, he plans a project with two hectares of tomatoes, two hectares of peppers, and one hectare of lettuce and other leafy vegetables. Not in pyramids, but in gutters. With solar panels and water filtration, Marnix wants to grow independently and self-sufficiently. The plan includes full energy and water self-sufficiency.

But before that can happen, money is needed; borrowing from banks is not an option in Suriname. That means looking for investors. Interest exists because demand is so high that, despite inflation, prices remain strong. "The market is asking for it. Not only in Suriname, but also in the region. Aruba, Curaçao, Guyana, everywhere there is demand for fresh vegetables that don't need to travel thousands of kilometers first," says Marnix. Still, he is not rushing, although he moves forward with determination. "If I follow my father, I have at least another 20 years before slowing down. So we will continue for a while."

For more information:  © Pieter Boekhout | FreshPlaza.com

© Pieter Boekhout | FreshPlaza.com

Marnix Maenhoudt (managing director)

Intergreens NV

Mahadjan Ram Adhinweg 57

Ornamibo Wanica (Suriname)

Tel: +597 829 24 16

[email protected]