While many farmers in Oregon are reducing activity due to tariff uncertainty, low crop prices, and labour constraints, some producers continue to invest in perennial crops. At Christensen Farms near Amity in Yamhill County, hazelnut grower Jeff Newton plans to plant additional hazelnut trees, reflecting a broader trend in the Willamette Valley.

Hazelnut growers in Oregon are awaiting final data on volumes sold in 2025, but acreage figures and preliminary indicators point to continued expansion. Although hazelnuts require a high upfront investment and several years before first production, the crop is gaining area at a time when overall farmland under cultivation is declining.

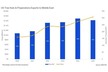

According to U.S. Department of Agriculture census data, land used for crop production in Oregon fell by about 1 million acres, or roughly 404,686 hectares, between 2002 and 2022. Over the same period, hazelnut acreage increased by 180 percent, from 31,000 acres, approximately 12,545 hectares, to 88,000 acres, around 35,612 hectares. In contrast, crops such as pears and cherries followed the wider downward acreage trend.

"The biggest driver is more consistently bad prices on all other crops," said Newton, vice chair of the Oregon Hazelnut Commission. "There just isn't a lot of other profitable crops to grow."

Planting tree crops involves long-term decision-making, as returns are not immediate. Tim Delbridge, assistant professor at Oregon State University's College of Agricultural Sciences, said farmers investing in perennial crops are making forward-looking assessments. "Maybe the farmer is thinking, 'Well, you know, I think hazelnuts have a bright future, and even though it costs a lot now, you know, I'm going to go ahead and invest in that,'" he says.

Despite risks such as disease pressure and delayed returns, hazelnut production continues to increase. Oregon is one of the world's leading hazelnut-producing regions and harvested an estimated 115,000 to 125,000 tons in 2025, according to Christine Roth, executive director of the Oregon Hazelnut Commission. Roth expects production volumes in the state to triple over the next six to seven years as newly planted orchards reach maturity.

The Willamette Valley's climate is considered suitable for hazelnut production, and many orchards remain family-operated across generations. Growers often maintain close relationships with processors, which is viewed as a way to manage quality and supply consistency.

"There's definitely that sense of, we're doing something special here," Roth says. "This is part of the fabric of Oregon."

Source: The New Era Newspaper