"There is a drop in the mango harvest. Mangoes no longer taste that sweet. Mangoes are expensive. Mangoes are arriving too early in the market. The mango pickle doesn't last through the year. The mango plant is flowering too early," are some of the anecdotal conversations about mangoes in India over recent years. This raises questions about potential links to higher temperatures.

According to the India Meteorological Department (IMD), the Annual Climate Survey of 2024 indicates a +0.65°C rise above the 1991–2020 average, marking 2024 as the warmest year since 1901. IMD data reveals that the last 12 years have been warmer, deviating from historical temperature fluctuations.

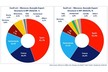

While anecdotal evidence suggests climate impacts on mango productivity, empirical data from India's Horticulture Department shows variability. Between 2001–02 and 2024–25, productivity ranged from 5.5 MT/Ha in 2008–09 to 9.7 MT/Ha in 2017–18, averaging 7.9 MT/Ha. In 2024–25, it is anticipated to reach 9.4 MT/Ha, surpassing China's 8.74 MT/Ha and Thailand's 8.36 MT/Ha.

The Agricultural Market Intelligence Centre at Professor Jayashankar Telangana State Agricultural University reports increased mango cultivation. In 2023–24, acreage rose by 2.34% to 2.401 million hectares, with production at 22.42 million tons, compared to 20.87 million tons from 2.346 million hectares the previous year.

Environmental stress from higher temperatures remains under study. "Higher temperatures cause fruit drop, early maturity, sun scalding, and uneven ripening in mango. In a variety like Alphonso, spongy tissue disorder will be seen," notes Naga Harshita Devalla from the College of Horticulture in Hyderabad.

Indian researchers, led by Rajdeep Haldar, highlight genetic diversity in mango production in response to climate change. "Mangoes possess physiological mechanisms that allow them to adjust and thrive in diverse and demanding environments," states their research.

Source: The Hindu